Tracing the history of colonial powers in Tamil land through charts and maps

Author Name

S. Jeyaseela Stephen

Published on

Sep 12 2025

The arrival of the Portuguese, Dutch, Danes, English and the French to the Tamil Coast and the history of cartography had been explored to a limited extent. Numerous forts and buildings were erected in the White Town of the European settlements. These were neatly separated by demarcating the boundaries of the Black Town. The European overseas commercial expansion led to the preparation of coastal charts and maps. The hydrographical, geographical and cartographical knowledge of the Tamil coast and in the interior hinterland obtained by the European traders and missionaries who were at the forefront has not till now been received adequate attention in historical research.

Map as a depiction on flat piece of paper of different types of physical spaces (land, oceans and mountains) calculated to scale had emerged in the age of expanding European commerce on the Tamil coast. The westerners carved up vast region of Tamil country on maps by drawing a straight line across terrain they had seen. They prepared coastal charts which were for restrictive use because they featured sensitive information. They never wished the navigational charts to fell into the hands of rival trading companies. These charts had marked the depth of water or dangers that lurked below the surface at high or low tide. They largely assisted the sea-captains and helped the pilots.

The Europeans developed a more sophisticated system of obtaining the primary geographic knowledge of Tamil coast at that time and they played significant role in preparing and publishing numerous maps. We need to examine the various phases and particular styles of making maps, the changes that came into technology, and the ways in which geography was studied.

With the process of Portuguese colonization, the sailors at first prepared maps and they laid emphasis in demonstrating the alternative methods which developed in sailing in the ocean safely depending on the monsoon and weather conditions. They prepared maps mainly mapping space and direction. The audience in Europe came to know the Tamil region and of their Christian missions. Maps enabled the missionary travellers on land to reach a variety of chosen destinations. In this process there had developed transmission and exchange of geographical knowledge between the Tamil Coast and the Atlantic region leading to the sophisticated cartographic system and practice. Map as graphic representation that facilitated a spatial understanding of things, concepts and processes in the trading world eventually led to mathematical construction as ‘scientific’ maps culminating in the ‘scale’ maps of the modern age leading to as a tool for the colonial game.

The map of the Portuguese colony of Devanampattinam (1607), Nagapattinam maps (1635-1658), Santhome of Mylapore maps (1635-1687) and the topographical map of Santhome of Mylapore in 1749 are found at the Centre for History and Old Cartography in Lisbon, Portugal. We notice interestingly the rise of Portuguese illuminated cartography.

The maps of fort Dansborg in Tranquebar (1669–1671) are found in the Royal Library, Copenhagen, Denmark. Christoph Theodosius Walther the Lutheran missionary at Tranquebar in 1734 was engaged in fixing the latitude and longitude of places in Tamil Country. He helped in producing maps by supplying geographical information for map-making in Denmark and Germany (1729-1745).

The maps and plans of the Dutch trading factories of Pulicat, Nagapattinam, Sadurangapattinam, Porto Novo and Punnaikayal are found in the Overseas Collection of Maps at the National Archives, The Hague in the Netherlands.

The plans and maps of Pondicherry prepared (1701-1789) are preserved at the Overseas Archival Centre at Aix-en-Provence in France. The Carnatic wars, the course of events and the Anglo-French supremacy for power during 1746 and 1761 led the French geographic engineers to make military journey and they prepared the maps and plans of the places, sieges, battles and wars fought. The French collection of the maps and plans of Pondicherry and Karaikal besides many places in Tamil countryside are significant. These had been preserved at Aix-en-Provence. Some of the plans and maps are also stored at the zonal office of the National Archives of India in Puducherry.

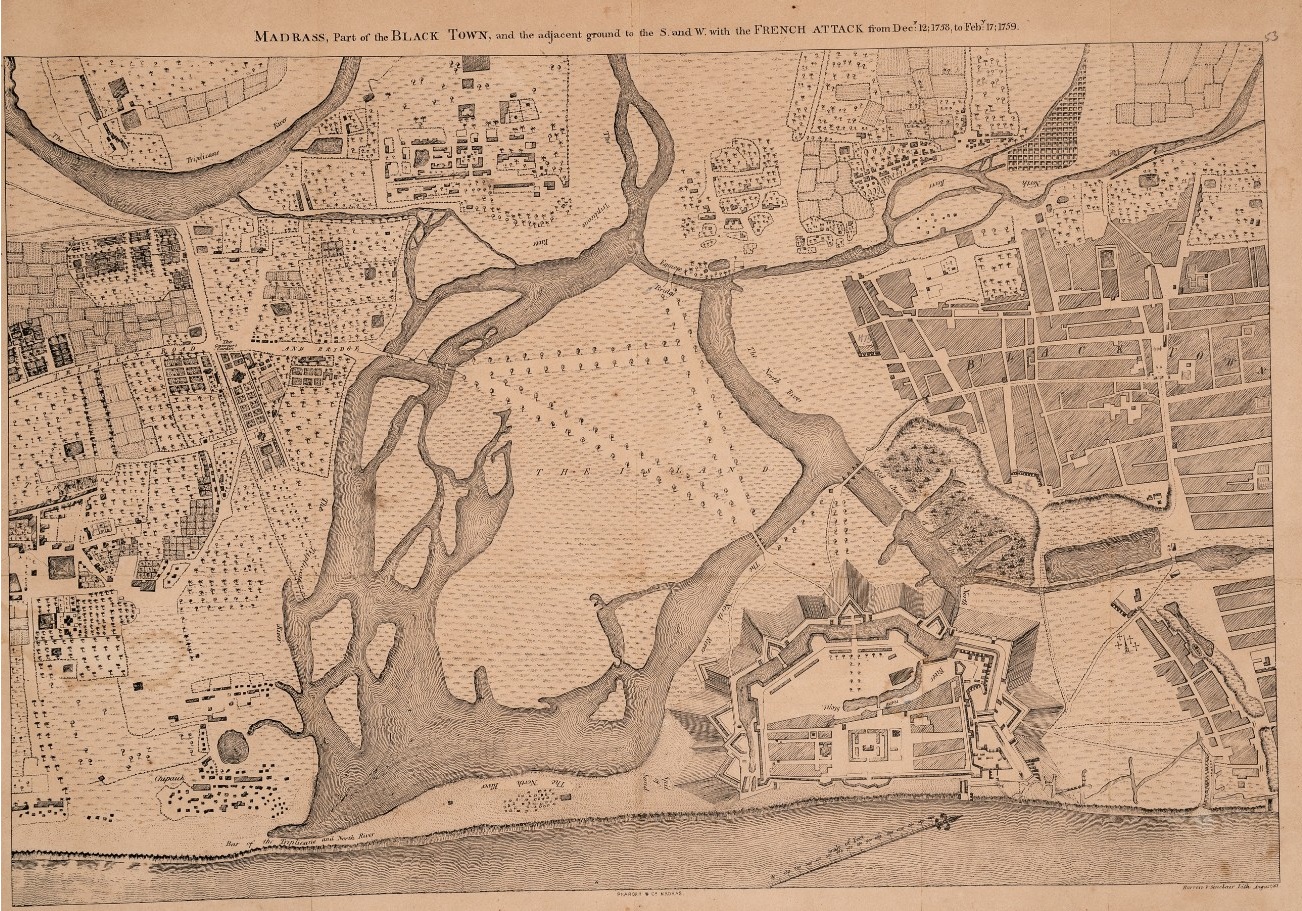

The English East India Company in Madras employed draughtsman and map-makers and they drew the plans of Madras, and the battles, wars and the military maps in the Carnatic (1745-1781). The land revenue surveys made by the British in Tamil Country led to the colonial strategy of systematic mapping (1767-1857. The various charts, views, plans and diagrams of Tamil coast prepared between 1798 and 1802 are found in the collection of Alexander Dalrymple at the Royal Naval Museum in Portsmouth.

The collection of maps and plans preserved at the Tamil Nadu State Archives, Chennai is very significant because they remain unused and under-utilized. The digitalization undertaken and the process completed now is a mile stone in the preservation of archival records.

The study of colonial history is in a perpetual state of change and development, with new fields of research constantly unfolding before our eyes. It has begun to build up and guided by multiple facets of human life that had been influenced through long distance maritime trade and commerce by the East India Companies, missionary expansion, military and territorial expansion, collection of revenue and through display of science and technology. Using maps and charts as new methods, we could explore and understand how colonialism played its own role. It is hoped that this and other new perspectives on colonial history would further continue to develop into sharp focus in the distant future.

- courtesy: The Hindu.

To view the maps click here